I attended the meeting at Boston University about Commonwealth Avenue in the evening of December 9, 2014. It was a day of unusually heavy rain. I got to the meeting about 1/2 hour late because of delays on the MBTA Riverside light rail line. Buses were running between Fenway and Kenmore stations while a barrier was being constructed to prevent the Muddy River from flooding the tunnel, causing millions of dollars in damage as happened 18 years ago in October 1996. (Better late than never…) The train stopped three times and waited for several minutes each time, between stations so I could not get off.

When I arrived at the meeting, Jeff Rosenblum from the Cambridge Community Development Department had already spoken. Pete Stidman of the Boston Cyclists Union was speaking. Stidman used Paul Schimek’s study of crashes on Commonwealth Avenue to promote sidepaths for crash reduction. This was opposite Schimek’s conclusion.

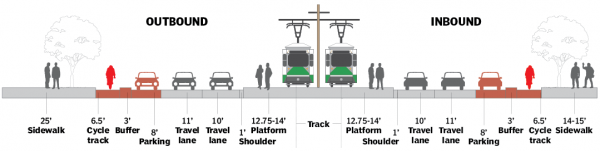

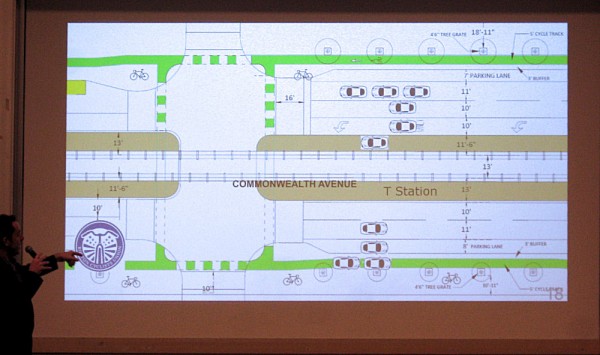

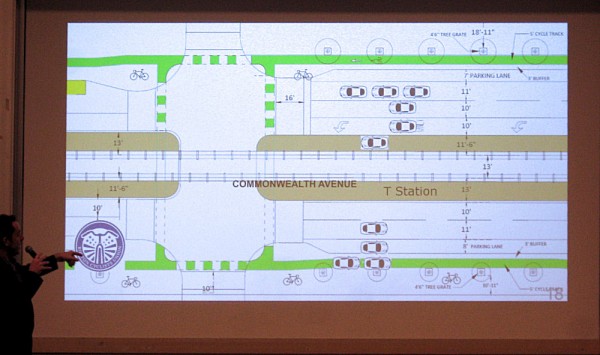

Stidman showed a street cross section with 8-foot parking lanes, 11-foot curb right-hand travel lanes; the other travel lanes would be 10 feet wide. In the image below, bicycle sidepaths (not “cycle tracks” — they are at sidewalk level) are in green. Bicyclists would cross streets in crossbikes adjacent to crosswalks.

If you look carefully at the drawing, you might also notice some odd things about it.

For westbound motor traffic, there is what I call a “musical chairs” intersection. Three travel lanes go in, but only two go out. So, motorists would have to merge from three to two lanes inside the intersection, looking back for overtaking traffic while also checking for crossing bicyclists and pedestrians.- Cars are shown parked on the median waiting area for the T station, and in one of the sidepaths.

- Bicycle symbols are strewn around at odd locations.

Charlie Denison (see his comment) has pointed out that the left lane westbound is a turn lane and that the issues with misplaced vehicles and symbols appear to have resulted from an error in formatting the drawing.

(You can click on the drawing to enlarge it, if you like).

Street cross section as described by Pete Stidman

By narrowing the roadway to place the sidepaths at sidewalk level, as on Vassar Street in Cambridge, this design would literally be set in stone.

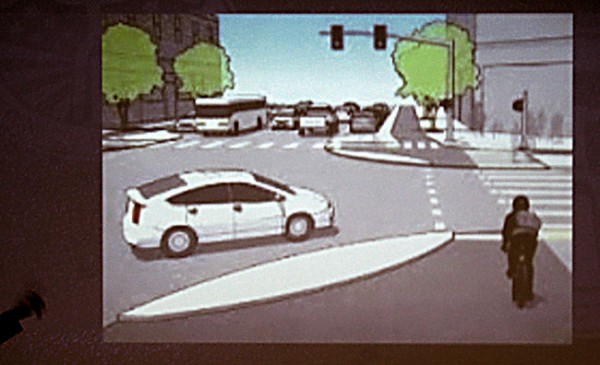

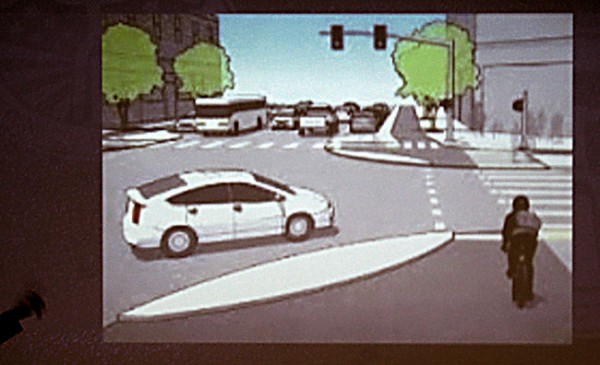

Stidman praised an intersection design which would set back the sidepaths from the side of the roadway so one turning car would have room to wait and yield to a bicyclist. If a second car or a longer vehicle had to wait, it would block through traffic on the roadway. This already happens with pedestrians, but bicyclists add to the delay, and are at greater risk because they approach the intersection at higher speeds, so they are hidden from turning motorists by other bicyclists and pedestrians waiting to cross in crosswalks. As I’ll discuss later, the temptation to ride opposite the direction of traffic will be irresistible — and entering an intersection opposite the direction of traffic is highly hazardous.

Pete Stidman shows a plan for right-turning traffic to yield to through-traveling bicyclists.

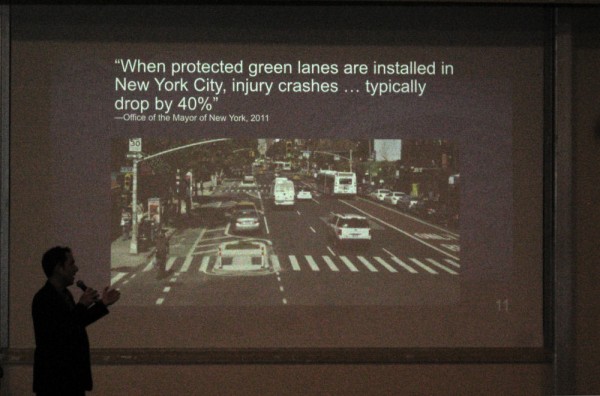

Stidman also cited a New York City report of a 40% reduction in crashes when a cycle track was installed (not saying what kinds of crashes or which cycle track); also data claiming an increase in business on 9th Avenue in Manhattan.

Stidman cites New York report

The devil is in the details. I’ve said nice things about the 9th Avenue bikeway, especially its ample width and signalization at all intersections — though it does have flaws. There are other New York City on-street separated bikeways which are thoroughly unsuccessful. I have comments, photo galleries and videos of several New York bikeways online, in case you wish to explore that topic further.

Robert Sloane from WalkBoston spoke next and expressed support on grounds that cycle tracks would make things better for pedestrians. He suggested the MIT campus as a counterexample to the BU campus: both are along the Charles River and with a major highway between the campus and the river, but the MIT campus has internal routes for bicycling, wide sidewalks and sidepaths, on Vassar Street. (Actually, the BU west campus is completely cut off from the riverfront by the Turnpike. East of the BU bridge there are only two overpasses over Soldiers Field Road, one of which has ramps, the other, stairs. The MIT campus connects to the riverfront with several crosswalks.) Sloane said nothing about the potential for internal routes on and near the BU campus, which I think hold great promise and which I have discussed at length on this blog.

A young woman from Massbike spoke, extolling the purported economic benefits of increased bicycle mode share.

A representative of BU spoke, and Traffic Commissioner Gillooly from the City of Boston also spoke. Of note, they both praised the efforts of BU Bikes, the regional advocacy organizations and the commenters, but they made no design commitment. The BU presenter described BU’s efforts to date, consisting of the construction of bike lanes and the reinforcement of their message (motor vehicles keep out, bicyclists stay in) with retroreflective pavement markers.

Following the presentations, the first commenter came on stage with her 5 year old daughter and supported the sidepaths because they would supposedly make Commonwealth Avenue a safe place for her 5 year old to ride. She described an incident with a close pass from a trucker when she was riding with her daughter.

The first commenter

Most commenters expressed that the sidepaths would improve conditions on Commonwealth Avenue. There were several who described the sidepaths as a solution to the problems with doorings, and having to merge out to overtake vehicles which had stopped in the bike lane.

There were a few commenters who expressed various light criticisms. Nobody spoke up in outright opposition to the sidepaths or described alternatives to them. Bicyclist Rebecca Albrecht was the most negative, expressing that the proposed sidepaths were too narrow at 5 feet and that faster bicyclists would not be able safely to overtake slower ones: sidepaths the Netherlands are 6 1/2 feet, and are being widened to 8 feet. One commenter who lives near the west end of the project objected to the longer walking distances which would be required to cross from Naples Road to Shaw’s Supermarket with the installation of a 1000-foot median barrier.

I had signed up to comment, but having arrived late, I was one of several people unable to comment because the meeting time ran out.

I attended the post-meeting party at Landry’s bicycle shop and talked at length with Jeff Ferris, owner of Ferris Wheels bicycle shop, who also had arrived at the meeting (later than I did — in the rain and by bicycle). Jackie Douglas of Livable Streets was in on the discussion of parallel routes and expressed that “that’s huge” — though Livable Streets was one of the organizations supporting the sidepaths.

I made an audio recording of the part of the meeting I attended and I’d be happy to share it. A video was recorded by Brilliant Gem Productions: contact person is Alex Nenopoulos, reachable at nenopoulos.com.

My opinions remain as expressed in my letter of October 14. Last night’s meeting revealed design details which highlighted the following issues for me, which I’m sure are troubling to the City:

-

-

- Narrow lanes proposed by the advocates and promoted as a way to reduce travel speed will increase friction and the risk of collisions. The lane widths proposed by Pete Stidman are not wide enough safely to accommodate a bus or truck with protruding mirrors. In the images below the truck and bus are nearly kissing mirrors.

- Also rather than there being a bike lane in the door zone, motorists in the right-hand travel lane will be driving in the door zone. Motorists who have parked will be unable to open a door or safely to walk around their vehicles if there is traffic in the next lane. I’ve modified the illustrations below from ones by Keri Caffrey. The vehicles in the travel lanes are a transit bus and and large truck. In the first drawing, the parked vehicle is a Toyota Camry. Its driver’s side door would strike the side of the bus if opened. In the second drawing, the vehicle is a Ford F150 pickup truck — for better or worse, the highest-selling motor vehicle. Its width is typical of larger vehicles which park on Commonwealth Avenue.

The Toyota Camry’s door would strike the side of the bus if opened.

The driver could not open the door far enough to exit the Ford F150 .

-

-

-

- Reducing the traveled width of Commonwealth Avenue to two narrow lanes eastbound will result in a reduction to one lane whenever a trucker has to stop to make a delivery, or anyone double-parks or has a breakdown, or there is a crash, or as I have already indicated, when more than one vehicle is waiting to turn right.

- Commonwealth Avenue is a major bus route. How are buses to stop without, again, blocking a travel lane? The sidepath promoters repeatedly mentioned the need to get more people to use public transportation, but they never mentioned how to accommodate bus stops.

- As Rebecca Albrecht stated, the proposed 5-foot sidepaths would be too narrow by Dutch standards, and certainly too narrow to accommodate bicyclists traveling at different speeds.

- The claim that the narrow sidepaths would keep bicyclists off the sidewalks is unrealistic, also because the sidepaths are intended for one-way travel. Many cyclists will ride opposite traffic on the sidewalk rather than to cross 5 travel lanes and the Green Line median to use the cycle track on the far side of Commonwealth Avenue. The alternative would be to ride away from their destination, make a U-turn to the opposite cycle track, ride past their destination and make another U turn before finally reaching their destination.

- Safety claims fall apart due to the unavoidable temptation to ride opposite traffic on sidewalks to avoid crossing the avenue twice for many trips. The image below, from an August, 2009 Google Street View, illustrates the temptation. A light service vehicle, probably one from Boston University, is traveling eastbound in the newly-installed westbound bike lane.

Light electric vehicle in bike lane on Commonwealth Avenue

-

-

- The temptation could be removed by providing a parallel route under the Boston University Bridge, as I have suggested. All in all, safe and low-stress bicycling in this corridor could be accommodated on parallel streets, not Commonwealth Avenue. The cycle track proposal, as is common with bicycling advocacy as of late, reflects not vision, looking toward optimal solutions, but opportunism, stuffing compromised and inadequate measures into a funded project.

There is to be another meeting, an actual design public hearing, probably in January.

See also:

Paul Schimek’s Facebook post about Commonwealth Avenue

BU Today story about the meeting