I am sick at heart.

Last December we lost Chris Weigl, graduate student in journalism at Boston University, a young man of great promise, killed when a semitrailer truck ran over him on Commonwealth Avenue near the BU campus. The green arrow approximates Weigl’s line of travel; the red arrow, the truck’s. (Also see larger Bing map.)

I’ve already posted more extended comments about Weigl’s crash on this blog, and there have been a number of thoughtful responses to that post.

On Sunday, May 19, we have had another major loss to society: Kanako Miura, visiting scientist at MIT and Japanese astronaut candidate finalist. She had to be very special to rise that far. Here, where Bay State Road splits off to the right of Beacon Street (also, see reconfigurable Google map):

Where Beacon Street comes out from under the Bowker overpass at the top of the picture, there is an unmarked shoulder (red arrow in picture) to the right of the bike lane, and motorists are expected to bear right across the bike lane to enter Bay State Road. It’s a messy intersection, with expanses of pavement that allow turning without slowing — but also, the dashes next to the bike lane extend way past where a driver would normally initiate a right turn onto Bay State Road.

I haven’t seen a report yet, but the crash is described as having occurred on Beacon Street — and yet video coverage shows police markings in the striped triangle (no-drive zone) between Beacon Street and Bay State Road; also, police lines and Miura’s smashed bicycle on Bay State Road. Probably, the truck and Miura were both headed west (toward the bottom of the picture) on Beacon street, and the truck turned right across Miura’s path to enter Bay State Road.

The truck driver claims never to have seen Miura, suggesting that the truck was initially going slowly, or stopped, and Miura was passing it on the right. The trucker may have initiated his right turn late, unexpectedly crossing the bike lane and the triangle. That could be tempting, for example, if traffic was congested a block ahead in Kenmore Square: it is possible to drive a couple of blocks on Bay State Road and turn left, then right to continue on Commonwealth Avenue.

The Miura and Weigl crashes are only the most recent among what is shaping up as an epidemic of serious and fatal truck-bicycle collisions in the Boston area.

In an attempt to avoid more such tragedies, let’s look at some specifics of right-turning truck crashes.

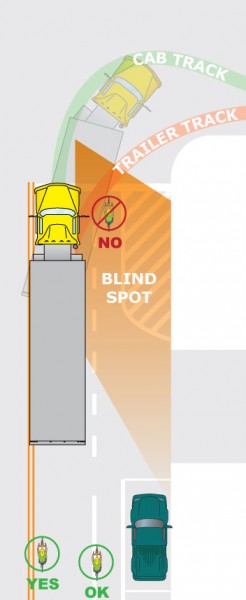

Humans have clear vision in only one direction at a time, but a trucker about to negotiate a turn has to look into several different mirrors, and also must scan ahead. Trucks have huge blindspots, and a bicyclist riding next to a truck may not always be visible in any mirror.

To the sign on the back of trucks, “If you can’t see my mirrors, I can’t see you,” I would add: “if you can see my mirrors, I still might not see you.”

The trucker in the Miura crash clearly was breaking the law, and confounded expectations about right of way if he turned into an area where driving is prohibited. But, regardless of the legalities, does it make sense for a bicyclist to hand over all responsibility for his or her own safety to the trucker?

A right-turn conflict is almost always foreseeable — and, having anticipated it, a bicyclist can prevent the collision. That Weigl and Miura were brilliant academics does not translate to their having had any instruction in how to look out for their safety on a bicycle.

Instruction exists. The City of London, England, has detailed advice including this graphic:

CommuteOrlando in Florida has the page, What Bicyclists Need to know About Trucks, including the graphic at the right. On that page, Keri Caffrey describes how she easily avoided the same situation which killed Weigl — truck turning right from the left lane.

The advice is clear and simple: don’t overtake into the danger zone next to a truck.

The two drawings below convey the same message. You may have seen them already.

Just in case you might discount the London and Orlando advice as Not From Here, those drawings are copied from pages 100 and 101 of the Massachusetts Driver’s Manual (pages 22 and 23 in the PDF of Chapter 4).

The second drawing portrays the exact situation which led to Chris Weigl’s crash, only showing a car instead of Weigl.

If the information in the Driver’s Manual is important for motorists, isn’t it even more important for cyclists, who are more vulnerable?

On the other hand: here is the pitch which advocacy organizations and bicycle program managers are making to the public: You fear motor vehicles, so we will provide a bike lane for you. Bike lanes make people feel safe and encourage them to to start riding. Then thanks to a “safety in numbers” effect, safety will increase because drivers will look more carefully. Oh, and also: bicycling’s health benefits far outweigh the risks.

All true, but it didn’t do anything for Chris Weigl or Kanako Miura and it doesn’t assure your safety either. It isn’t reasonable to overtake into the area next to the truck where the wheels will offtrack over you if it turns, and place your complete trust in the driver not to turn across your path. A statistical improvement and a feelgood promise are no substitute for the specific, on-the-spot choices which keep you out of danger.

There’s a sharp divide in the bicycling community.

On the one hand, some bicyclists — I’m one — practice defensive driving, and apply the rules of the road to make ourselves visible and predictable.

This behavior is self-reinforcing. As soon as a bicyclist takes it up, the rate of close calls and unpleasant encounters plummets. A bicyclist gets the satisfaction of being a good citizen using the public roads responsibly and legally. This extends to validation in maneuvering in ways which the striping does not suggest — for example, passing a truck on the left with plenty of clearance. It is legal to ride outside a bike lane, after all. There’s no law against waiting behind the truck either. Notice that, please. This isn’t about riding fast, as many detractors would like to insist. It is about riding smart.

On the other hand, there is the mentality which equates cyclists’ vulnerability with defenselessness. The many close calls which result from naively following the edge of the road, or the painted stripe –“letting the paint think for you” — suggest that any other choice would be more dangerous — a vicious cycle which traps cyclists in this behavior. As this translates into advocacy, I suppose that if you believe that cyclists are defenseless anyway, enticing them to ride into the danger zone doesn’t feel any less ethical than encouraging them to ride anywhere else. Maybe you believe that it’s all for the greater good, though there will be a few sacrifices along the way.

On the third hand, many cyclists opportunistically violate the rules which make travel predictable. And so do many motorists. And pedestrians. But that’s a topic for another article.

Now the City of Boston and Boston University, on whose doorstep both the Weigl and Miura fatalities occurred, propose to take their infrastructure approach to safety one step further. A painted bike lane isn’t enough: now it will have reflectorized markers. These will probably make drivers somewhat more attentive, but they cannot eliminate blindspots and will reinforce the impression that the bike lane assures safety. Most kinds of reflectorized markers are a trip-and-fall hazard for bicyclists, too, see the video here and comments here.

And yes, some cyclists — children — are defenseless. Their parents need to understand the risks and make choices about where they may ride. In any case, the cyclists who have been dying are adults.

Let me also make it clear that I have no general opposition to bike lanes, no matter what some people say about me. Bike lanes can make for a real improvement in appropriate locations and with appropriate design. For example, you may read my comments about Charles River Road in Watertown. The issue I have is with unsafe design, airy promises and failure to distribute life-saving information.

I have made specific suggestions, on this blog, for some low-cost and effective infrastructure improvements in and around the Boston University campus. These would serve less confident cyclists — even children — much better than the bike lanes do, and offer an alternative to the very nasty intersection at Commonwealth Avenue and the BU bridge.

We need to do better. There have been too many sacrificial lambs in this campaign.